An article written by Dr Edward Leatham, Consultant Cardiologist © 2025 E.Leatham

An AI audio construct is available as a podcast for this story below.

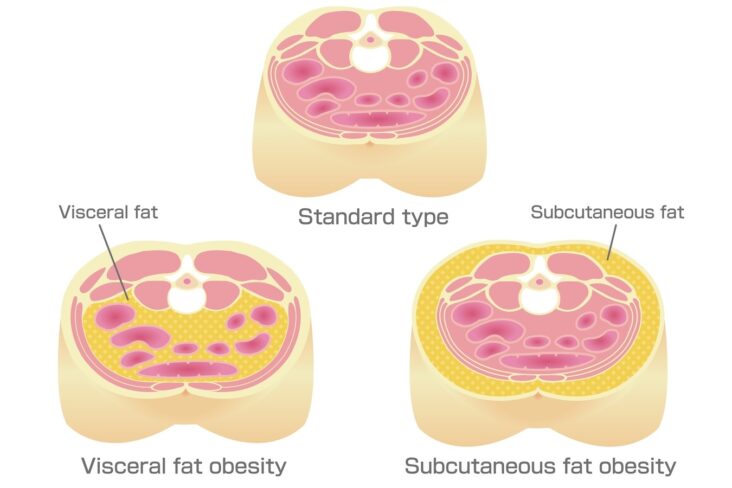

Tags: Mens Health, Visceral Fat, Coronary heart disease, search website using Tags to find related stories.

For over two decades, coronary artery calcium (CAC) scoring has been used as a quick, low-cost, low-radiation screening tool for identifying subclinical coronary artery disease. However, recent advances in cardiovascular imaging, growing understanding of plaque biology, and shifts in preventive cardiology have challenged its continued use in younger patients.

At our clinic, we no longer recommend CAC scoring as a screening test for men under 50 and women under 60. Here’s why.

1. Low Sensitivity for At-Risk Younger Adults

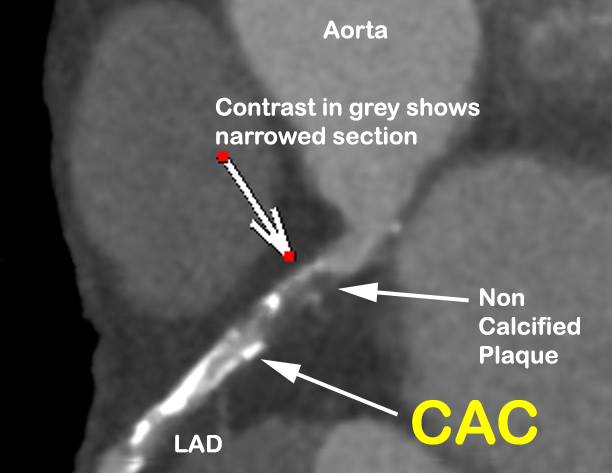

CAC scoring detects calcified plaque, which represents only 10–20% of total coronary plaque volume in early and intermediate stages of disease¹. The remaining 80–90% of plaque is non-calcified, and this is particularly true in patients under 60. These early-stage plaques are vulnerable, inflammatory, and prone to rupture—even if they are not yet calcified.

We’ve seen too many patients in their 40s and 50s with significant non-calcified coronary plaque and a CAC score of 0. These individuals are often falsely reassured and do not get started on statins or lifestyle interventions when, in fact, they are at meaningful risk.

2. Lack of Correlation Between CAC and Vessel Narrowing

CAC does not measure stenosis or obstructive disease. It reflects the burden of calcification, not plaque volume, vulnerability, or flow-limiting disease. Numerous studies confirm that there is no direct correlation between CAC score and angiographic stenosis severity².

This limitation severely restricts the clinical utility of CAC in personalising risk or guiding therapy in younger adults.

3. Poor Predictive Value of Serial CAC Scans

Tracking CAC progression over time has little predictive value. An increase in CAC may reflect disease progression—or it may reflect healing, as statins and LDL lowering often promote plaque calcification as a stabilisation mechanism³. Repeating CAC scans does not provide actionable insight, nor does it alter clinical decisions in most cases⁴.

Because of this, serial CAC testing is not recommended by major guidelines⁵.

4. Radiation Dose, Though Low, Must Be Justified

The effective radiation dose of a typical CAC scan is 0.8–1.5 mSv⁶—comparable to a mammogram, and lower than a standard CT angiogram. While this is low, any exposure to ionising radiation must be justified, especially in younger adults, where CAC is often absent and the scan is non-informative.

By contrast, a modern CT coronary angiogram (CTCA) can now be performed at 2.0–4.0 mSv with contemporary dose-reduction techniques⁷. For just a modest increase in radiation, CTCA provides vastly more information—identifying non-calcified plaque, assessing stenosis, and, increasingly, inflammation metrics like the **Fat Attenuation Index (FAI)**⁸.

5. FAI and Plaque Imaging Are the Future of Risk Stratification

One of the most exciting advances in cardiovascular imaging is the ability to detect coronary inflammation using the perivascular Fat Attenuation Index (FAI). Available as early as age 30, FAI provides predictive value beyond calcium or cholesterol, identifying at-risk individuals even in the absence of plaque⁹.

This imaging biomarker gives us a functional window into plaque activity, not just structure. When paired with plaque morphology and volume from CTCA, we can now offer personalised prevention strategies far earlier and more accurately than CAC alone ever could.

6. Statins Promote Calcification — And That’s a Good Thing

Ironically, one of the goals of lipid-lowering therapy is to stabilise plaque through calcification. Statins help convert soft, high-risk plaques into dense, calcified, low-risk structures¹⁰. As such, the presence of calcification may reflect prior healing—not current risk.

This further undermines the logic of relying on CAC in younger patients, whose plaques are often early-stage, lipid-rich, and uncalcified.

Conclusion: Time to Move On

In 2025, with access to low-dose CT angiography, FAI analysis, and a deeper understanding of plaque biology, it is increasingly difficult to justify CAC scoring in younger individuals.

- Due to low sensitivity at younger age CAC has much lower overall predictive value in those under 50 (men) or under 60 (women).

- A score of 0 does not mean “no risk”

- Calcification is not the enemy—instability is

Given the modest but real radiation dose and the high false reassurance rate, continuing to offer CAC to younger patients may no longer be ethical, especially when more informative tools are available.

If the goal is early identification and prevention, CTCA with plaque and FAI analysis is the new standard—and CAC is best reserved for selected older patients where calcified burden more closely tracks with overall risk.

References

- Dey D, et al. Association of epicardial and thoracic adipose tissue with coronary artery plaque burden. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2010;3(10):1020-1029.

- Yeboah J, et al. Comparison of novel risk markers for improvement in cardiovascular risk assessment. JAMA. 2012;308(8):788-795.

- Puri R, et al. Effect of statins on plaque composition. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015;65(13):1298-1310.

- Blaha MJ, et al. Serial measurement of coronary artery calcium. JACC Cardiovasc Imaging. 2016;9(3):386-396.

- Hecht HS, et al. 2021 ACC/AHA guideline update for CAC scoring. Circulation. 2021;143(21):e973-e987.

- Einstein AJ, et al. Radiation dose from cardiac imaging. Circulation. 2007;116(11):1290-1305.

- Williams MC, et al. CT coronary angiography: dose reduction and image quality. Eur Heart J Cardiovasc Imaging. 2013;14(10):958-963.

- Oikonomou EK, et al. Non-invasive detection of coronary inflammation using CT and FAI. Lancet. 2018;392(10151):929-939.

- Antonopoulos AS, et al. Detection of inflammation in atherosclerosis with imaging. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020;17(8):479-496.

- Nicholls SJ, et al. Statins and plaque calcification. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;62(1):21-29.

Other related articles

- The CaRi Heart Score: A New Frontier in Cardiovascular Risk Assessment