An article written by Dr Edward Leatham, Consultant Cardiologist

For busy people, or to tune in when on the move, Google Notebook AI audio podcast and an explainer slide show are available for this story beneath.

Tags: VAT, Metabolic Health, MASLD, search website using Tags to find related stories.

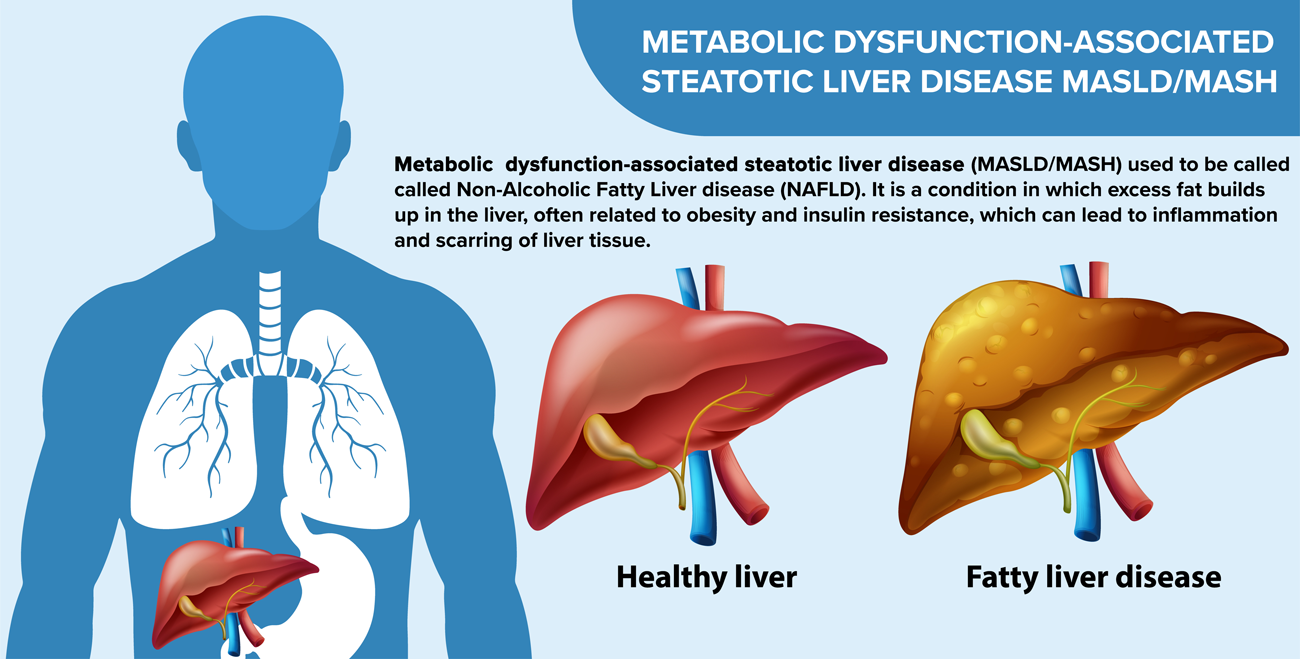

MASLD and MASH are related liver conditions, with MASLD (metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease) being a broad term for fat buildup in the liver, and MASH (metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis) being a more severe form in which the fat is accompanied by inflammation and liver cell damage.

MASLD was formerly known as non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), and MASH was formerly known as non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH). They are now among the most common liver conditions worldwide and the leading cause of abnormal liver blood tests in the UK.

The conditions are closely linked to insulin resistance, raised visceral adipose tissue, and metabolic syndrome — the same cluster of factors that drive type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular disease.

What Is MASLD?

MASLD refers to the build-up of fat (triglyceride) within the liver — a condition known as hepatic steatosis — occurring in people who do not drink alcohol excessively.

To make this diagnosis, doctors use alcohol intake thresholds of:

- Less than 20 g per day (≈ 2.5 units) for women

- Less than 30 g per day (≈ 3.75 units) for men

When alcohol intake is below these levels, and excess fat is detected in the liver, the condition is classified as non-alcoholic.

The Spectrum of MASLD

MASLD is not a single condition, but a spectrum that ranges from harmless to serious:

- Simple steatosis – seen in up to 90% of people with NAFLD. Fat accumulates in the liver cells, but there is little inflammation or damage. Prognosis is usually good.

- Non-alcoholic MASH (metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis) – a more severe form, where inflammation and liver cell injury occur. MASH increases the risk of fibrosis, cirrhosis, and, in rare cases, liver cancer (hepatocellular carcinoma).

Symptoms

Most people with MASLD are asymptomatic, meaning they feel well and the condition is discovered incidentally during routine blood tests or scans.

When symptoms do occur, they are often non-specific, such as:

- Fatigue or low energy

- General malaise

- Discomfort or fullness in the upper right side of the abdomen

How Is MASLD Diagnosed?

MASLD should be suspected when a person has risk factors for metabolic disease and abnormal liver blood tests lasting three months or longer. Typically:

- Alanine aminotransferase (ALT) is raised (up to 3× the upper limit of normal)

- Aspartate aminotransferase (AST) is normal or lower than ALT

An ultrasound scan of the upper abdomen can confirm fatty infiltration of the liver, showing a “bright” or echogenic liver consistent with steatosis.

Further non-invasive tools, such as FibroScan or MRI-based liver fat quantification, may be used to assess the degree of fibrosis or inflammation.

Risk Factors for MASLD

MASLD shares the same drivers as metabolic syndrome. Risk factors include:

- Central obesity (increased waist circumference or visceral fat)

- Type 2 diabetes or impaired glucose regulation

- High blood pressure (hypertension)

- Raised cholesterol or triglycerides (hyperlipidaemia) in. fasting blood sample

These factors are closely interlinked through insulin resistance, the same process that drives fat accumulation in the liver and other organs.

Complications of MASLD

Liver-related complications

- Fibrosis and cirrhosis (scarring of the liver)

- Portal hypertension and variceal bleeding

- Liver failure

- Hepatocellular carcinoma (liver cancer)

Metabolic and cardiovascular complications

- Type 2 diabetes

- Cardiovascular disease — which is, importantly, the leading cause of death in people with NAFLD

This means that managing MASLD is not just about protecting the liver — it’s also about protecting the heart.

Lifestyle and Prevention

The cornerstone of MASLD management is metabolic improvement through lifestyle change- for more information see blogs beneath on how to reduce VAT.

- Weight reduction — even a 5–10% loss of body weight can reduce liver fat and inflammation

- Waist measurement — aim for a waist-to-height ratio below 0.5

- Healthy diet — focus on:

- Low-glycaemic, high-fibre foods

- Reduced refined sugars and processed carbohydrates

- Adequate protein intake to preserve muscle

- Regular physical activity — both aerobic exercise and resistance training help improve insulin sensitivity and reduce visceral fat

- Avoid excess alcohol — even moderate intake can worsen liver inflammation in those with NAFLD

In some cases, medications or clinical trials targeting insulin resistance and liver inflammation may be considered under specialist guidance.

When to Seek Medical Advice

Speak to your GP or get in touch using our ENQUIRE NOW form if you:

- Would like to order liver function tests at our clinic or at home using our home blood test service.

- Have persistently abnormal liver tests and need a scan

- Have risk factors for metabolic syndrome you would like to discuss

- Are overweight around the waist despite your best efforts

- Have type 2 diabetes or elevated blood sugar levels

Early detection allows for lifestyle and metabolic interventions that can halt or reverse liver fat accumulation and significantly reduce cardiovascular risk.

In Summary

MASLD is a silent but important marker of metabolic health.

Although often discovered by chance, it carries significant implications for both liver and cardiovascular wellbeing.

Through weight control, physical activity, improved nutrition (is VAT-reduction), MASLD can often be stabilised or reversed — protecting not just the liver, but the heart as well.

Related posts

- How to Lose Visceral Adipose Tissue (VAT) and Improve Metabolic Health: A Guide to Sustainable Weight Loss

- Visceral Fat, Mitochondria, and the Energy Trap: Why We Store Fat Where We Shouldn’t

- Why everyone is talking about VAT

- Intervention programmes: from self-toolkits to nurse-led escalation to GLP-1 support

- GLP-1 mimetic clinic

- The GLP-1 Mimetic Clinic