An article written by Dr Edward Leatham, Consultant Cardiologist for his VAT-TRAP series featured under this metabolic health blog.

For busy people, or to tune in when on the move, Google Notebook AI audio podcast and an explainer slide show are available

We live in an age where every opinion can be broadcast instantly to millions.

This has brought enormous progress in communication — but also a new kind of danger: the mass spread of half-truths and pseudoscience. Few examples are more striking than the explosion of anti-statin material online, often presented by confident voices with persuasive language, selective data, and little or no accountability.

For many patients, particularly those without access to doctors they know and trust, the result is confusion — and in some cases, harm. People stop taking the very medication that could prevent their next heart attack or stroke, based on messages that sound scientific but collapse under proper scrutiny.

How selective bias distorts the truth

One of the greatest challenges in the online world is investigator bias.

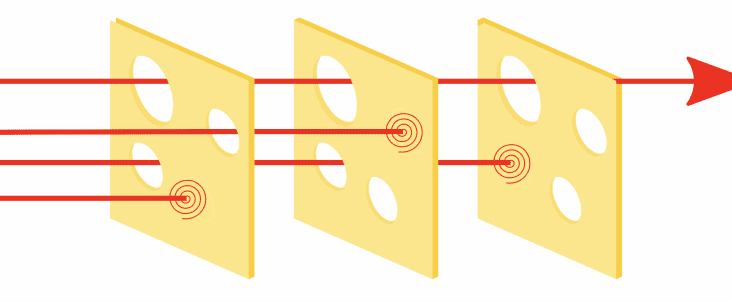

Any “expert” with a strong conviction — whether pro- or anti-statin — can easily find studies that appear to confirm their view. The internet is full of such cherry-picked data.

When presented with confident authority, this can sound utterly convincing to a lay audience.

The reality is that true medical understanding does not come from one paper, one YouTube video, or one self-proclaimed authority.

It comes from a systematic, unbiased review of all the evidence — the kind of process carried out by large-scale meta-analyses, Cochrane reviews, and formal application of the Bradford Hill criteria for causation.

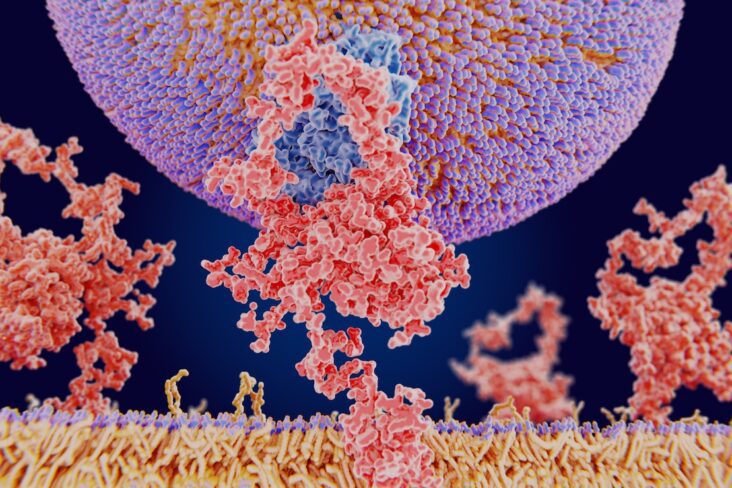

When that broader and more rigorous approach is taken, the conclusions are clear: LDL cholesterol is causal in atherosclerosis, and lowering it reduces the risk of heart attack and stroke in a predictable, dose-dependent manner. It’s true that the cause of raised LDL is a matter of great debate and truthfully probably varies according to population and prevalence of insulin resistant states that drive metabolic rises in LDL. However this does not alter the fact that in higher risk individuals, drug therapies such as statins form an important part of the prevention of coronary heart disease.

That conclusion does not invalidate the role of inflammation or visceral adipose tissue (VAT) — both matter — but it firmly establishes LDL as a key modifiable driver of risk.

Why some patients lose faith in the system

Part of the problem lies within medicine itself.

Many doctors, through no fault of their own, follow national guidelines and Department of Health policies without necessarily having the time or resources to explore the complex mechanisms behind every recommendation.

They are also constrained by short consultation times, heavy workloads, and administrative pressure — all of which make it difficult to have the deep, open discussions patients want and deserve.

This can create an unfortunate vacuum.

When a patient’s legitimate questions about statins or cholesterol remain unanswered, they go looking elsewhere — and the internet is ready to fill that gap with confident, unregulated opinions.

The issue is compounded by the gradual disappearance of the traditional family doctor — the GP who cared for generations within one household and built trust over decades.

Now, many people report that “I see a different doctor every time.”

Continuity of care has been sacrificed to system efficiency, and we may one day look back on this as a major turning point in medicine — a moment when trust, not technology, became the scarcest resource in healthcare.

Good medicine is not built on policy alone. It is built on trust, communication, and mutual understanding. Without those foundations, compliance and long-term health outcomes will always suffer.

Personalised vs population-based medicine

Another layer of confusion arises from the tension between population-based guidelines and the new era of personalised medicine.

National guidelines are designed to protect the greatest number of people, often by identifying those at statistically higher risk based on age, blood pressure, cholesterol, and other broad measures.

Age, in particular, is the most powerful predictor of cardiovascular events — which is why so many older adults are recommended statins even if they feel well and have only modest LDL elevation.

This population-level approach saves lives overall, but it can feel impersonal to an individual sitting in front of their doctor.

The recommendation can sound algorithmic rather than tailored — “your risk score says you need a statin” — which again can erode trust.

In our clinic, we have a major advantage: alongside a full range of lipid and metabolic function tests including fasting insulin and CGM profiling used to determine carbohydrate sensitive genotype. We have onsite access to advanced cardiac CT imaging, including coronary calcium scoring (CAC), CT angiography to detect presence location and characteristics of coronary plaque, fat attenuation index (FAI) analysis to quantify coronary inflammation and low dose VAT CT to quantify visceral adipose tissue in anyone with heart disease whose waist circumference exceeds half their height.

These technologies allow us to measure plaque burden, arterial inflammation, and metabolic risk directly.

With that information, we can move from generic population guidance to personalised risk stratification — and therefore, a much more informed conversation about the true need for statin therapy.

For many patients, seeing the data from their own arteries provides the clarity and reassurance that no guideline leaflet can deliver.

Understanding the root causes — and treating both

It is also essential to recognise that elevated LDL is sometimes a consequence of underlying metabolic dysfunction.

When the waist-to-height ratio exceeds 0.5, it is likely that visceral fat is contributing to an atherogenic lipid profile — raised LDL, low HDL, and elevated triglycerides — through mechanisms involving PCSK9 activation and hepatic overproduction of lipoproteins.

In such cases, focusing solely on statins may be insufficient.

For lower-risk patients, especially those without calcified plaque or significant arterial inflammation, targeting the root cause through VAT reduction can meaningfully improve lipid balance without long-term medication.

This is achieved through carefully designed nutritional strategies, resistance training, sleep optimisation, and real-time metabolic feedback using continuous glucose monitoring (CGM).

In other words: the goal should not be to choose between statins and lifestyle — but to match the treatment to the cause, and to use technology to guide those decisions accurately.

Rebuilding trust in the age of misinformation

To rebuild trust, both doctors and patients must adapt.

Doctors need to make time for meaningful dialogue, and patients need to be encouraged to question information constructively — not to reject expertise outright, but to seek clarity from qualified sources.

Reliable guidance comes from clinicians and organisations who:

- Are regulated and accountable — answerable to the GMC and inspected by the CQC.

- See thousands of patients each year, providing perspective grounded in real outcomes, not theory.

- Have no commercial incentive to promote a supplement, diet trend, or particular medication.

- Use transparent patient feedback (e.g. Trustpilot) to ensure ongoing accountability.

- Collaborate across disciplines — cardiology, lipidology, and diabetology — to interpret new evidence fairly.

- Are guided by data and imaging, not ideology.

These are the clinicians the public can truly trust — those who operate within a high-governance framework, whose professional integrity is tested daily in the care of real people.

Practical guidance for navigating online information

- Check credentials. Is the person giving advice medically qualified and regulated?

- Look for references. Are statements supported by recognised journals or meta-analyses, not anecdotes?

- Identify conflicts of interest. Does the source profit from a supplement, device, or subscription?

- Beware of extremes. Claims that “all statins are poison” or that “cholesterol doesn’t cause heart disease” are hallmarks of bias.

- Discuss before deciding. Always talk to your clinician before stopping or starting any medication.

The road back to trust

Medicine has never been more technologically capable, yet trust has rarely felt so fragile.

The modern internet can make every voice sound equal — but in health, expertise still matters.

True medical progress is made not through loud opinions, but through open-minded, unbiased evaluation of all the evidence, interpreted through real clinical experience.

At the Surrey Cardiovascular Clinic, we combine this scientific rigour with advanced imaging and patient-centred care — ensuring that recommendations are not just guideline-compliant, but genuinely personalised.

That is how trust is rebuilt: one conversation, one scan, one well-informed decision at a time.

So before accepting health advice online, ask yourself one simple question:

If this person is wrong, will they be there to face the consequences with me?

If the answer is no — close the tab, and speak to someone who will.

Technical papers: located in Dr Leatham’s “VAT Trap” Digital Companion and Resources (free to download)

- Online Statin Narratives — The Prevalence of Misinformation and Potential Harm in Coronary Prevention

- Bradford Hill’s Criteria for Causation Applied to LDL Cholesterol and Coronary Heart Disease

- A Bradford Hill Appraisal of Raised Visceral Adipose Tissue and Coronary Heart Disease:

- Debate: This House Believes That LDL Cholesterol Is a Bystander — Not a Cause — of Coronary Heart Disease

Related posts

- Cholesterol, LDL, and what we learnt from PCSK9 mutations in familial hypercholesterolaemia

- PCSK9, visceral fat, and the modern metabolic environment

- So what does determine your LDL (‘bad’) Cholesterol?

- LDL: the lower the better