An article written by Dr Edward Leatham, Consultant Cardiologist © 2025 E.Leatham

Tags: VAT, CGM, Metabolic health, Diabetes, NH1, search website using Tags to find related stories.

For busy people, or to tune in when on the move, Google Notebook AI audio podcast and an explainer slide show are available for this story beneath.

If you have ever found yourself feeling breathless climbing stairs or walking uphill — even though your lung and heart tests are “normal” — you are not alone.

Many people attribute it to age or fitness. But recent research has uncovered a powerful hidden cause of breathlessness: visceral fat — the fat stored deep inside your abdomen, around your organs.

In this blog, we will explore what visceral fat is, how it affects your breathing, and — most importantly — what you can do about it.

🧠 What is Visceral Fat?

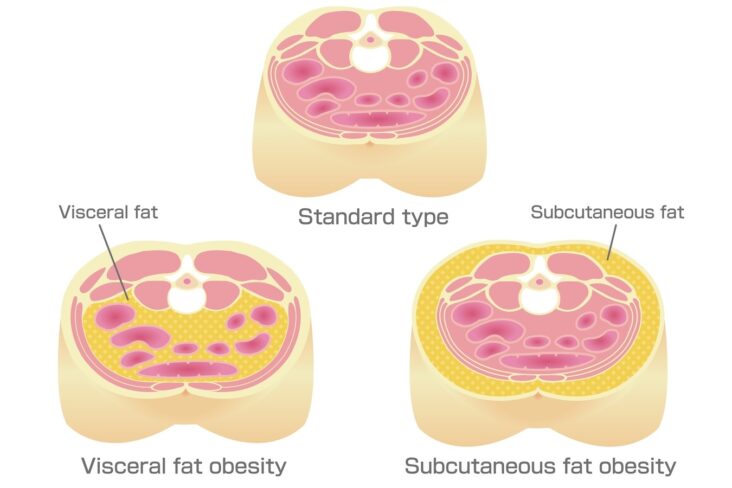

When we think of body fat, we usually imagine the soft fat we can pinch under our skin — that is called subcutaneous fat. But visceral fat is different. It lies deep inside your belly, surrounding your liver, pancreas, intestines, and other vital organs.

Visceral fat is not just sitting there. It acts like a hormone-producing organ, releasing inflammatory chemicals and interfering with your metabolism, blood pressure, and even your breathing¹.

We measure visceral fat using a scan — usually a CT — which gives a value called VATI (visceral adipose tissue index). A high VATI means you are storing too much fat around your organs — and that can have serious consequences for your heart, lungs, and quality of life².

💨 How Does Visceral Fat Make You Breathless?

You may be wondering: how can fat inside my belly affect how I breathe?

Here are five key ways high visceral fat contributes to shortness of breath — even in people with no obvious lung or heart disease:

1. It Physically Restricts Your Breathing

Visceral fat increases pressure in the abdominal cavity. This pushes up on your diaphragm (the main breathing muscle), especially when you are lying down or bending over³. That means:

- Your lungs cannot fully expand.

- You take shallower breaths.

- You feel like you are not getting enough air — especially during exertion.

This is known as restrictive breathing and is a common but under-recognised effect of central obesity⁴.

2. It Makes Breathing More Effortful

With excess belly fat, your respiratory muscles — including the diaphragm and chest wall — have to work harder to move air in and out.

This means your body uses more energy just to breathe. It can leave you feeling fatigued and breathless with even mild activity, like walking or doing housework⁵.

3. It Increases the Risk of Heart Dysfunction (Especially HFpEF)

High visceral fat is closely linked to a type of heart problem called heart failure with preserved ejection fraction (HFpEF).

In HFpEF:

- The heart pumps well but does not relax properly between beats.

- This leads to raised pressures in the lungs, especially during exertion.

- The result is exertional breathlessness even though the heart appears “normal” on basic tests⁶ ⁷.

This condition is more common in people with central obesity, diabetes, high blood pressure, or fatty liver disease — all of which are linked to excess visceral fat⁸.

4. It Is Associated With Low Fitness and Muscle Loss

High VAT is often part of a pattern called sarcopenic obesity — where people have high belly fat and low muscle mass⁹.

The result?

- Less muscle means lower exercise capacity.

- Even everyday activities can leave you out of breath and tired.

- It becomes a vicious cycle: the more breathless you feel, the less you move — and the weaker your muscles become.

5. It Promotes Chronic Inflammation and Metabolic Dysfunction

Visceral fat releases inflammatory chemicals that affect how your body uses oxygen and responds to exercise. It also contributes to conditions like:

- Fatty liver (NAFLD)

- Insulin resistance

- Sleep apnoea

All of these can increase fatigue and reduce your oxygen efficiency, making you feel more breathless during the day¹⁰ ¹¹.

🔬 “But My Tests Are Normal” — When Breathlessness Feels Unexplained

Many people with high visceral fat undergo lung function tests, ECGs, chest X-rays, or even heart scans — and are told everything looks normal.

But these tests often miss the subtle effects of visceral fat. They do not always pick up early diastolic dysfunction or reduced lung volumes from mechanical restriction⁶.

That is why it is important to look beyond the numbers and ask:

- Is there excess visceral fat?

- Is fitness and muscle strength low?

- Is there undiagnosed metabolic stress on the heart or lungs?

Sometimes, we need to look at the bigger picture, not just individual test results.

📏 How Do I Know If I Have Too Much Visceral Fat?

You do not need a CT scan to suspect excess visceral fat. Here are some useful clues:

✅ Waist-to-Height Ratio (WHtR)

A simple tape measure can give a good estimate. Aim for:

- Less than 0.5 (waist circumference should be less than half your height)

- Over 0.55 suggests excess visceral fat and higher cardiometabolic risk¹²

✅ Body Shape

- An apple-shaped body (more fat around the middle than hips/thighs) is more likely to have high VAT.

- You can be a “normal weight” on the scales and still have excess visceral fat — known as TOFI (thin outside, fat inside)¹³.

🧭 What Can I Do About It?

The good news? Visceral fat is responsive to change — even more so than surface fat.

Here is how to start reducing VAT and improving your breathing:

1. Track Your Waist, Not Just Your Weight

Use waist circumference and waist-to-height ratio to monitor your progress. Many people notice:

- Waist shrinking before weight drops significantly

- Improved breathing and energy within weeks¹⁴

2. Eat to Support Fat Loss and Muscle Strength

Focus on:

- Higher protein intake to support muscle and satiety

- Fewer ultra-processed carbohydrates (e.g. white bread, biscuits, sugary snacks)

- Time-restricted eating or lower evening carbohydrate intake may help some people

Apps like Dr Shape or MyFitnessPal can help track macronutrients¹⁵.

3. Move More — Especially Resistance Training

Cardio is helpful, but building muscle is key for VAT reduction and improving your breathing.

Aim for:

- 2–3 resistance sessions per week

- Simple home-based bodyweight workouts

- Daily walking or cycling to build baseline aerobic fitness¹⁶

4. Track Progress With Digital Tools

Consider:

- Body composition scales (to track visceral fat estimates)

- Waist measurements

- Fitness tracking apps to monitor improvements in activity and breathlessness

If appropriate, your doctor may use:

- Hilo wrist BP monitors to assess blood pressure control

- Sleep study to assess whether you have sleep apnoea, another powerful association with high VAT and breathlessness

- CGM (Continuous Glucose Monitoring) to reduce blood sugar spikes

- CT scans to track VATI reduction over time

5. In Some Cases, Medical Therapy Helps

For some individuals, especially those with:

- Persistently high VATI on imaging

- Breathlessness limiting daily life

- Coexisting diabetes or fatty liver

… your doctor may discuss medications that support VAT reduction, such as GLP-1 receptor agonists¹⁷.

These medications have been shown to reduce visceral fat, improve diastolic function, and support weight loss — especially when combined with lifestyle change.

🔑 Key Takeaways

- Visceral fat can restrict breathing, reduce fitness, and affect your heart.

- If you are breathless but tests are “normal,” high visceral fat may be the missing piece.

- Waist-to-height ratio is a simple, powerful tool to estimate risk.

- Reducing VAT through diet, resistance training, and sometimes medical therapy can dramatically improve breathlessness and long-term health.

📚 References

- Wajchenberg BL. Subcutaneous and visceral adipose tissue: their relation to the metabolic syndrome. Endocr Rev. 2000;21(6):697–738.

- Kim SK, Cho JY, Park SW, et al. Visceral fat measured by CT scan and the risk of coronary artery disease. J Korean Med Sci. 2004;19(4):588–592.

- Pelosi P, Croci M, Ravagnan I, et al. The effects of body mass on lung volumes, respiratory mechanics, and gas exchange during general anesthesia. Anesth Analg. 1998;87(3):654–660.

- Salome CM, King GG, Berend N. Physiology of obesity and effects on lung function. J Appl Physiol. 2010;108(1):206–211.

- Babb TG. Obesity: challenges to ventilatory control during exercise—a brief review. Respir Physiol Neurobiol. 2013;189(2):364–370.

- Obokata M, Reddy YNV, Pislaru SV, et al. Evidence supporting the existence of a distinct obese phenotype of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circulation. 2017;136(1):6–19.

- Shah SJ, Kitzman DW, Borlaug BA, et al. Phenotype-specific treatment of heart failure with preserved ejection fraction. Circulation. 2016;134(1):73–90.

- Neeland IJ, Ross R, Després JP, et al. Visceral and ectopic fat, atherosclerosis, and cardiometabolic disease: a position statement. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7(9):715–725.

- Prado CM, Wells JC, Smith SR, Stephan BC, Siervo M. Sarcopenic obesity: a critical appraisal of the current evidence. Clin Nutr. 2012;31(5):583–601.

- Kuk JL, Katzmarzyk PT, Nichaman MZ, Church TS, Blair SN, Ross R. Visceral fat is an independent predictor of all-cause mortality in men. Obesity. 2006;14(2):336–341.

- Lonardo A, Ballestri S, Marchesini G, Angulo P, Loria P. Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease: a precursor of the metabolic syndrome. Dig Liver Dis. 2015;47(3):181–190.

- Ashwell M, Gibson S. Waist-to-height ratio as an indicator of ‘early health risk’: simpler and more predictive than using a ‘matrix’ based on BMI and waist circumference. BMJ Open. 2016;6(3):e010159.

- Thomas EL, Frost GS, Taylor-Robinson SD, Bell JD. Excess body fat in obese and normal-weight subjects. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(6):536–537.

- Redman LM, Smith SR, Burton JH, Martin CK, Il’yasova D, Ravussin E. Metabolic slowing and reduced oxidative damage with sustained caloric restriction support the rate of living and oxidative damage theories of aging. Cell Metab. 2018;27(4):805–815.e4.

- Hall KD, Kahan S. Maintenance of lost weight and long-term management of obesity. Med Clin North Am. 2018;102(1):183–197.

- Strasser B, Arvandi M, Siebert U. Resistance training, visceral obesity and inflammatory response: a review of the evidence. Obes Rev. 2012;13(7):578–591.

- Friedrich N, Thuesen BH, Jørgensen T, Juul A, Spielhagen C, Wallaschofski H. The association of gender and abdominal obesity with serum leptin concentrations: a population-based study. Obesity. 2008;16(3):749–755.

Other related articles

- Why the Mediterranean Diet Works: It’s More Than Just What You Eat

- Why everyone is talking about VAT

- How to Lose Visceral Adipose Tissue (VAT) and Improve Metabolic Health: A Guide to Sustainable Weight Loss

- The 8-Month Metabolic Reset: A New Approach to Reversing Visceral Fat, Improving Blood Pressure and Blood Glucose

- Five Reasons Why a Cardiologist Might Recommend a Continuous Glucose Monitor (CGM) to their Patient

The Naked Heart is an educational project owned and operated by Dr Edward Leatham. It comprises a series of blog articles, videos and reels distributed on Tiktok, Youtube and Instagram aimed to help educate both patients and healthcare professionals about cardiology related issues.

If you would like to receive email notification each week from the Naked Heart, follow me on social media or please feel free to subscribe to the Naked Heart email notifications here