An article written by Dr Edward Leatham, Consultant Cardiologist © 2026 E.Leatham

Tags: Mens Health, Genes, Coronary heart disease, search website using Tags to find related stories.

At Surrey Cardiovascular Clinic (SCVC), we can now use advanced genetic testing to understand how your body handles dietary fat — and why some people’s cholesterol levels rise more sharply than others when they eat foods rich in saturated fat.

We Do Not All Respond the Same Way to Fat

It has long been known that reducing saturated fat intake can help lower “bad” cholesterol (LDL-C) and reduce the risk of heart disease. However, not everyone responds in the same way.

Modern research has shown that genes strongly influence how much LDL cholesterol increases when you eat foods such as butter, cheese, or fatty meats, compared with foods rich in unsaturated fats like olive oil, nuts, and oily fish.

Even when two people eat the same diet, their cholesterol response can be very different — sometimes varying by as much as 1 mmol/L. This is because our genes influence both how cholesterol is absorbed from the intestine and how efficiently our cells clear LDL cholesterol from the bloodstream.

The ApoE Gene – A Major Determinant of Cholesterol Handling

One of the most important genes involved in cholesterol metabolism is Apolipoprotein E (ApoE).

There are three common versions of this gene — E2, E3, and E4 — and each affects how cholesterol moves into and out of cells.

- ApoE4 carriers tend to absorb more cholesterol from the intestine and have fewer LDL receptors on their cells. This means cholesterol remains in the bloodstream for longer, leading to higher LDL-C levels.

These individuals are usually more sensitive to saturated fat and cholesterol, so their LDL may rise sharply if they consume foods such as butter, cream, or processed meat. - ApoE2 carriers usually have more active LDL receptors, allowing cholesterol to be cleared from the blood more efficiently. Their LDL-C levels are often lower, and they may be less affected by dietary cholesterol or saturated fat.

Most people carry the ApoE3 form, which represents an average response.

Knowing your ApoE type can help to personalise your diet. For example, an E4 carrier may benefit from keeping saturated fat below 10% of daily energy intake and focusing on unsaturated fats from olive oil, avocados, and oily fish. An E2 carrier may not need to be quite as restrictive, although a Mediterranean-style pattern benefits almost everyone.

Other Fat-Related Genes Tested at SCVC

Our Nutrigenomix® DNA panel at SCVC includes several other genes that influence how you process fats:

- APOA2 – influences how much LDL-C increases in response to saturated fat.

- FTO – affects how your body weight and cholesterol respond to high-fat diets.

- PPARγ2 – influences how effectively your body uses monounsaturated fats such as olive oil.

- FADS1 – affects how well your body converts omega-3 and omega-6 fats, which in turn influences inflammation and heart health.

Together, these markers explain why one person can tolerate a higher-fat diet with little change in cholesterol, while another develops a noticeable rise in LDL within weeks.

The Cellular “Regulatory Pool” of Cholesterol

Inside each of your cells is a small pool of free cholesterol that acts as a sensor.

When this pool is low, cells pull LDL cholesterol from the bloodstream using LDL receptors. When it is high, they reduce uptake, allowing LDL levels in the blood to rise.

Your genes influence how large and sensitive this regulatory pool is. People who carry ApoE4 or certain LDL receptor variants tend to have a less responsive system, which can lead to higher circulating LDL even on modest amounts of saturated fat.

What This Means for You

Understanding your genetic profile allows your consultant to create a nutrition plan that works with your biology rather than against it.

For example:

- If you carry ApoE4, you may respond best to limiting animal fats and increasing omega-3-rich foods such as salmon or flaxseed.

- If you have certain APOA2 or FTO variants, attention to both fat quality and energy balance becomes especially important.

- If your FADS1 gene limits omega-3 conversion, regular oily fish or supplementation is strongly recommended.

Eating According to Your Genes

Genetic testing does not replace healthy eating advice — it personalises it.

By understanding how your genes interact with saturated and unsaturated fats, you can make informed choices to maintain healthy cholesterol levels and protect your heart.

If you would like to understand your genetic profile — including your ApoE type — contact Surrey Cardiovascular Clinic to arrange your Nutrigenomix® test. Your results will help us to design a nutrition and lifestyle plan tailored to your genetic makeup and cardiovascular risk.

Other related articles

- From Genes to Greens: How DNA Shapes Your Nutritional Needs

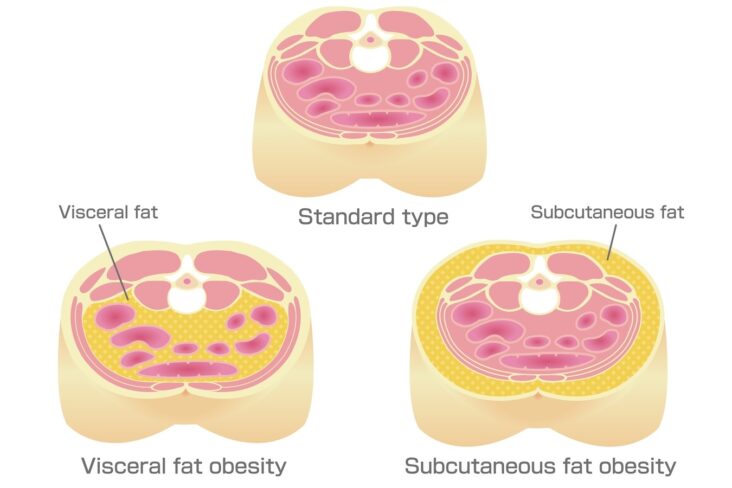

- Effects of different exercise types on visceral fat in young individuals with obesity aged 6–24 years old: A systematic review and meta-analysis 2022

- Clinical significance of visceral adiposity assessed by computed tomography: A Japanese perspective: 2014

- Visceral and ectopic fat, atherosclerosis, and cardiometabolic disease: a position statement 2019

- Body fat distribution on computed tomography imaging and prostate cancer risk and mortality in the AGES-Reykjavik study 2019