An article written by Dr Edward Leatham, Consultant Cardiologist

For busy people, or to tune in when on the move, Google Notebook AI audio podcast and an explainer slide show are available for this story beneath.

Tags: VAT, Metabolic Health, MASLD, search website using Tags to find related stories.

Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) — formerly non-alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) — has become one of the most common causes of abnormal liver blood tests worldwide, including the UK. Its more severe form, metabolic dysfunction-associated steatohepatitis (MASH) (previously NASH), is now a leading cause of liver fibrosis and cirrhosis.

With MASLD so prevalent, the reference ranges used for routine liver function tests (LFTs) have been affected. “Normal” values may no longer represent true hepatic health, as many reference populations now include individuals with unrecognised hepatic steatosis. This makes it vital to interpret results in context and to track changes over time rather than rely on a single value.

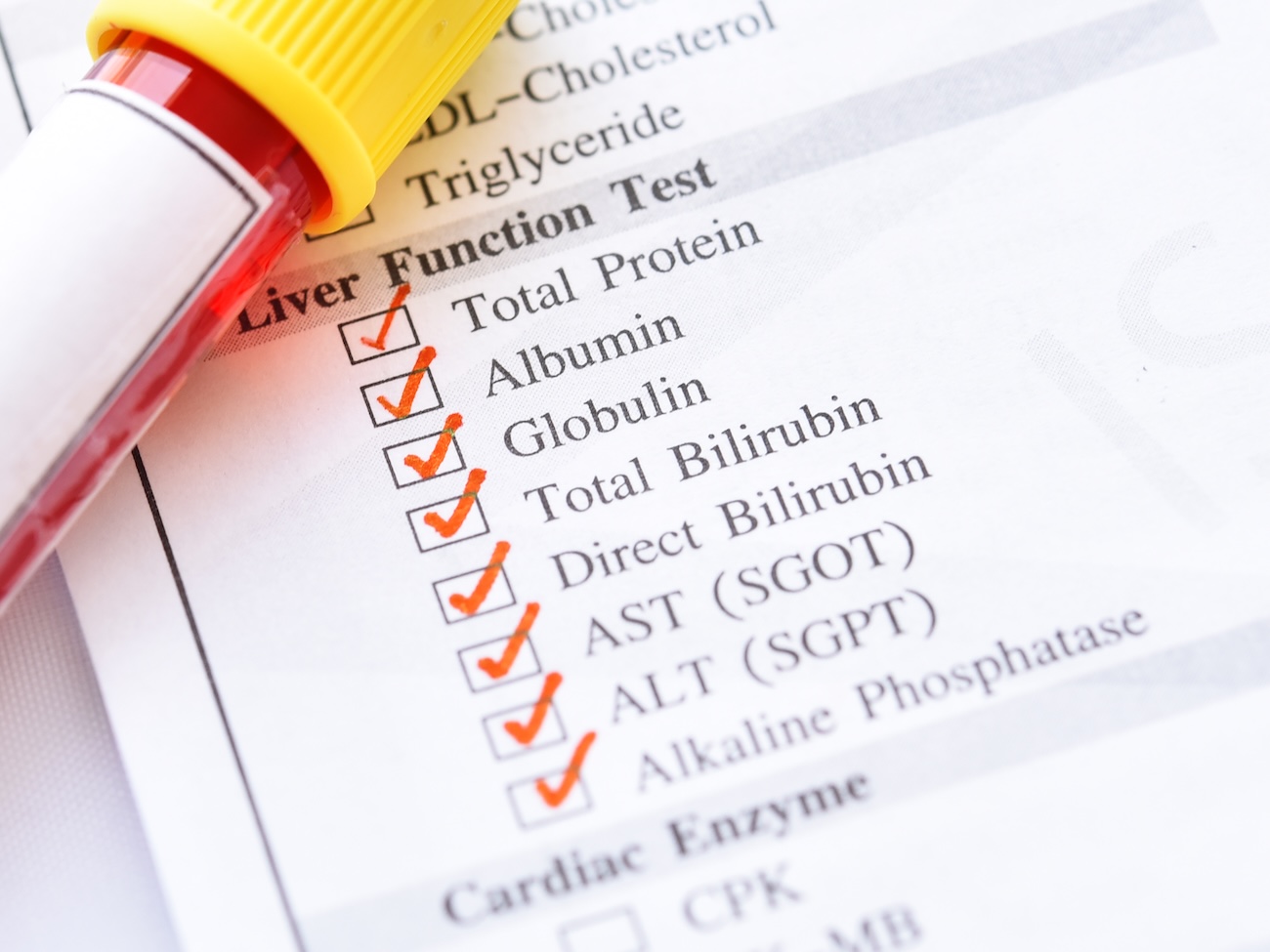

1. The Liver Tests Most Relevant to MASLD

A typical LFT panel includes:

- Alanine aminotransferase (ALT)

- Aspartate aminotransferase (AST)

- Gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT)

- Alkaline phosphatase (ALP)

- Bilirubin and albumin (as markers of hepatic function)

In early MASLD, ALT is often the first enzyme to rise, sometimes only modestly. Levels can remain “within normal limits” despite significant fat accumulation or even early fibrosis¹.

2. When “Normal” Isn’t Normal Anymore

Traditional upper limits for ALT (often ≤55 U/L in UK labs) were derived decades ago, before the epidemic of obesity and steatosis. Current evidence suggests these ranges are too high — and that values above 30 U/L may already indicate liver injury in people with metabolic risk²(https://rightdecisions.scot.nhs.uk/tam-treatments-and-medicines-nhs-highland/adult-therapeutic-guidelines/liver/metabolic-dysfunction-associated-steatotic-liver-disease-masld-primary-care-guidelines/).

The British Society of Gastroenterology (BSG) guidelines emphasise that a result within the “normal range” may not be reassuring if the patient is metabolically high-risk³(https://www.bsg.org.uk/getmedia/b51bdc64-7145-43ad-828b-21f473b0a918/Guidelines-on-the-management-of-abnormal-liver-blood-tests.pdf).

A longitudinal rather than snapshot approach is therefore key:

- Look for upward drift in ALT, AST, or GGT over time.

- Repeat testing every 6–12 months in at-risk patients.

- Correlate with anthropometric and metabolic parameters.

3. Insulin Resistance and Glucose Markers

MASLD is part of the insulin resistance spectrum. As resistance develops:

- Fasting insulin and HOMA-IR may rise.

- Fasting glucose may drift upward into the impaired range (≥5.6 mmol/L).

Even mild elevations should prompt review of liver enzymes, as hepatic steatosis is often the first metabolic organ affected⁴(https://britishlivertrust.org.uk/information-and-support/liver-conditions/masld-nafld-and-fatty-liver-disease/).

Tracking both LFTs and fasting glucose/insulin can reveal early metabolic stress long before overt diabetes or liver inflammation appear.

4. Waist-to-Height Ratio: A Window into Visceral Fat

A simple tape measure can be as informative as a blood test.

A waist-to-height ratio (WHtR) > 0.5 correlates strongly with visceral adipose tissue (VAT) — the main driver of insulin resistance and MASLD⁵(https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0177175).

NICE guidance now promotes the message:

“Keep your waist less than half your height.”⁶(https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Waist-to-height_ratio)

In a cardiometabolic clinic, combining WHtR with ALT trends can be an early, low-cost way to flag hepatic steatosis risk.

5. Lipid Clues: Triglycerides, HDL, and the Small Dense LDL Pattern

MASLD is not isolated to the liver — it reflects a systemic lipid trafficking problem.

As hepatic fat increases, VLDL (very-low-density lipoprotein) secretion rises, leading to:

- High triglycerides (>1.7 mmol/L or >150 mg/dL)

- Low HDL-cholesterol (<1.0 mmol/L in men, <1.2 mmol/L in women)

- Small dense LDL particles — more atherogenic despite “normal” LDL-C

This lipid pattern, known as atherogenic dyslipidaemia, is typical of insulin resistance and MASLD⁷(https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3872713/).

The LDL:HDL ratio can serve as a quick screening tool: a ratio > 2.5 (1.5 in afro caribbeans) suggests an adverse lipid pattern and potential hepatic fat accumulation⁸(https://lipidworld.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12944-018-0851-0).

6. Integrating Liver, Lipid, and Metabolic Data in the Cardiometabolic Clinic

In practice, consider MASLD whenever you see:

- Central adiposity (waist-to-height ratio > 0.5)

- Rising fasting glucose or insulin

- High triglycerides and low HDL (in a blood sample after a strict overnight fast)

- ALT creeping toward or above 30 U/L

Recommended actions:

- Request full LFTs (ALT, AST, GGT, ALP, bilirubin, albumin).

- Track trends over time — not just absolute values.

- Assess for fibrosis (e.g., FIB-4 score, transient elastography) if LFTs are persistently high.

- Address metabolic drivers — diet, resistance training, weight reduction, and VAT loss.

7. The Take-Home Message

MASLD is now so common that it distorts the very tests used to detect it. “Normal” ranges have drifted upward, meaning clinicians must look at the trajectory of liver enzymes, not just their current values.

By integrating liver tests, glucose and insulin trends, lipid ratios, and waist measures, cardiometabolic clinics can detect metabolic liver disease earlier — before irreversible fibrosis or cardiovascular complications arise.

References

- British Liver Trust. Liver blood tests – what do they mean? https://britishlivertrust.org.uk/information-and-support/living-with-a-liver-condition/liver-blood-tests/

- NHS Highland. MASLD (Metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease) primary care guidelines. https://rightdecisions.scot.nhs.uk/tam-treatments-and-medicines-nhs-highland/adult-therapeutic-guidelines/liver/metabolic-dysfunction-associated-steatotic-liver-disease-masld-primary-care-guidelines/

- Newsome PN et al. Guidelines on the management of abnormal liver blood tests. BSG, 2017. https://www.bsg.org.uk/getmedia/b51bdc64-7145-43ad-828b-21f473b0a918/Guidelines-on-the-management-of-abnormal-liver-blood-tests.pdf

- British Liver Trust. MASLD (formerly NAFLD). https://britishlivertrust.org.uk/information-and-support/liver-conditions/masld-nafld-and-fatty-liver-disease/

- Ashwell M, Gibson S. Waist-to-height ratio as an indicator of “early health risk”. PLoS One 2017;12(5):e0177175. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371%2Fjournal.pone.0177175

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. Keep your waist to less than half your height. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Waist-to-height_ratio

- Adiels M et al. Atherogenic dyslipidaemia and small dense LDL in metabolic syndrome. Lipids Health Dis 2013;12:128. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC3872713/

- Vekic J et al. Small dense LDL and cardiovascular risk. Lipids Health Dis 2018;17:121. https://lipidworld.biomedcentral.com/articles/10.1186/s12944-018-0851-0

Related posts

- MASLD/MASH -metabolic dysfunction -associated steatotic liver disease: What You Need to Know

- How to Lose Visceral Adipose Tissue (VAT) and Improve Metabolic Health: A Guide to Sustainable Weight Loss

- Visceral Fat, Mitochondria, and the Energy Trap: Why We Store Fat Where We Shouldn’t

- Why everyone is talking about VAT

- Intervention programmes: from self-toolkits to nurse-led escalation to GLP-1 support

- GLP-1 mimetic clinic

- The GLP-1 Mimetic Clinic