An article written by Dr Edward Leatham, Consultant Cardiologist

Tags: Syncope, AFib, NH1, ECG search website using Tags to find related stories.

When unexplained fainting episodes (syncope) or certain types of stroke occur, the search for an underlying cause can be frustrating for patients and clinicians alike. In some cases, the usual tests — ECGs, Holter monitors, echocardiograms — return entirely normal results, leaving us with more questions than answers.

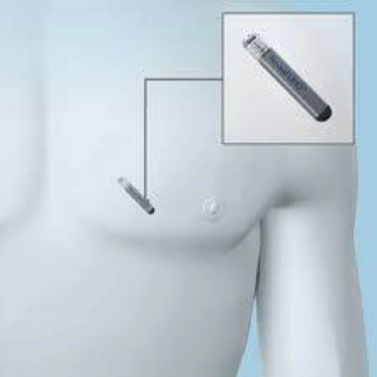

One increasingly important tool in solving these clinical mysteries is the implantable loop recorder (ILR) — a small device, implanted under the skin of the chest, that continuously records heart rhythm for up to three years. It has transformed our ability to detect rare, intermittent, and often silent heart rhythm problems that would otherwise go unnoticed.

This article will focus on ILRs in the context of syncope and cryptogenic (i.e., unexplained) stroke, TIA, and transient global amnesia (TGA) — with a particular emphasis on how they help detect subclinical atrial fibrillation and why that matters for stroke prevention.

Why We Investigate Heart Rhythm in These Conditions

The link between certain heart rhythm disorders and brain events is well established. In particular, atrial fibrillation (AF) and atrial flutter can cause blood stasis in the left atrial appendage (LAA), leading to blood clot formation.

Whether a clot forms depends on several factors:

- The shape of the left atrial appendage (some anatomical variants have more nooks and pockets where blood can stagnate)

- The duration of fibrillation or flutter episodes (longer episodes give more time for clot formation)

- Overall atrial function (weakened atrial contraction worsens stasis)

Once a clot forms, it can detach — embolise — and travel through the aorta into the arteries of the brain. If it lodges in an end artery, blood flow is blocked, causing a stroke or TIA.

The size of the embolus determines how large a brain artery is blocked. The brain’s natural fibrinolytic system may dissolve small clots quickly, leading to a TIA rather than a permanent stroke. But larger clots, particularly those blocking the middle cerebral artery, often cause severe, lasting neurological damage.

With modern medicine, thrombolytic therapy can sometimes dissolve such clots if given rapidly after stroke onset. Nonetheless, prevention remains far better than cure.

The Hidden Risk: Subclinical Atrial Fibrillation

Many people with atrial fibrillation have no idea they have it. This is because the atrioventricular (AV) node — the gatekeeper controlling electrical signals from the atria to the ventricles — behaves very differently in different people.

In some, the atrial rate during AF may be as high as 600 beats per minute, but the AV node allows through only a modest number of impulses, resulting in a ventricular (pulse) rate that feels almost normal. Without palpitations or breathlessness, AF can go entirely unnoticed.

Others have paroxysmal AF, where episodes come and go, sometimes lasting only hours or days before returning to a normal rhythm. This group is at particular risk of embolic stroke because even when the atria return to normal rhythm, there can be a period of atrial stunning — temporary mechanical inactivity of the LAA. During this time, pre-formed thrombus may be expelled into the circulation.

This explains why the highest risk period for embolic stroke after electrical cardioversion is around day two, unless anticoagulants are given.

Why Standard Monitoring Often Misses the Diagnosis

Because of the above mechanisms, it is customary to investigate all patients with TIA, TGA, or stroke with:

- A 12-lead ECG

- Ambulatory ECG monitoring (24- to 48-hour Holter, or longer patch ECG systems such as the Preventice device, which can record for up to two weeks)

However, even these extended tests may fail to capture rare AF episodes that happen only a few times a year — or even less frequently.

A Case Example: The Three-Year Wait for the Truth

Consider a 65-year-old woman who presented with a TIA. All her investigations — ECG, blood pressure monitoring, Holter ECG, transoesophageal echocardiography — were normal.

The recommendation was to start anticoagulation based on probability that AF might be the cause. However, the patient declined, wishing for definitive evidence. She instead had an ILR implanted.

For three years, no abnormal rhythms were recorded during routine checks or via the home monitoring system. Just before the device was due for removal, it was read one final time. The result? She had been in continuous AF for the preceding week.

Although extreme, this case illustrates a vital point: paroxysmal AF can be extremely rare yet clinically significant, and only long-term monitoring can reliably detect it.

ILRs in the Investigation of Syncope

ILRs are equally valuable in investigating syncope — sudden, brief loss of consciousness due to temporary lack of blood flow to the brain.

Syncope can be caused by:

- Sinus node dysfunction (long pauses or failure to initiate heartbeats)

- High-grade atrioventricular block

- Ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation

- Severe vasovagal episodes

If initial tests (including Holter or event monitors) are inconclusive, an ILR offers a much higher chance of capturing the heart rhythm at the exact moment symptoms occur — especially when episodes are infrequent, separated by weeks or months.

From a health-economics perspective, fitting an ILR after one or two negative ambulatory recordings is cost-effective compared with the repeated expense of hospital admissions for unexplained syncope. It also has major implications for driving restrictions — a confirmed diagnosis can mean a more precise risk assessment rather than indefinite precautionary bans.

How an ILR Works

An ILR is a matchstick-sized device implanted under the skin of the chest, usually under local anaesthetic in a brief outpatient procedure. Once in place, it continuously monitors the heart’s electrical activity, storing recordings of any abnormal events it detects automatically or when triggered by the patient using a handheld activator.

Modern ILRs have:

- Automatic arrhythmia detection algorithms

- Wireless home monitoring (transmitting daily summaries to the cardiology team)

- Battery life of 2–4 years

- MRI-compatibility in most cases

When to Consider an ILR

An ILR may be recommended if you:

- Have unexplained syncope with inconclusive standard tests

- Have had a cryptogenic stroke, TIA, or TGA, where AF is suspected but not proven

- Have infrequent but concerning palpitations that evade short-term monitoring

- Have suspected intermittent AV block or sinus pauses

Benefits and Limitations

Benefits:

- Captures very rare arrhythmias

- High diagnostic yield

- Minimally invasive procedure

- Improves confidence in diagnosis and treatment decisions

Limitations:

- Small risk of infection or device displacement

- May not detect events if they are not electrical in origin (e.g., purely vasovagal syncope without bradycardia)

- Requires follow-up and device interrogation

Preventing the First — or Next — Stroke

The ultimate goal of detecting subclinical AF is to prevent stroke. Once AF is confirmed, most patients at risk will benefit from anticoagulation to dramatically reduce the likelihood of a clot forming and travelling to the brain.

For patients with cryptogenic stroke, studies have shown that prolonged rhythm monitoring — particularly with an ILR — can double or triple the detection rate of AF compared with standard short-term monitoring.

Key Takeaways

- Atrial fibrillation and flutter can silently cause devastating strokes through clot formation in the left atrial appendage.

- Subclinical AF is common and often missed by standard ECG monitoring.

- ILRs offer long-term surveillance and have transformed diagnosis in patients with cryptogenic stroke/TIA and unexplained syncope.

- Detecting AF allows for life-saving anticoagulant therapy, tailored to individual risk.

- The investment in ILR technology is often outweighed by the prevention of future strokes and reduction in hospital admissions.

Final Word

For patients and clinicians facing the uncertainty of unexplained stroke or fainting, an ILR can be the missing piece of the diagnostic puzzle. It is not simply a piece of technology — it is a window into the heart’s behaviour over months and years, giving us the best chance of catching rare but dangerous arrhythmias before they cause harm.

Other related articles

- How AFib can present as a heart attack or stroke

The Naked Heart is an educational project owned and operated by Dr Edward Leatham. It comprises a series of blog articles, videos and reels distributed on Tiktok, Youtube and Instagram aimed to help educate both patients and healthcare professionals about cardiology related issues.

If you would like to receive email notification each week from the Naked Heart, follow me on social media or please feel free to subscribe to the Naked Heart email notifications here