An article written by Dr Edward Leatham, Consultant Cardiologist

Tags: VAT, CGM, Metabolic health, Diabetes, NH1, search website using Tags to find related stories.

For busy people, or to tune in when on the move, Google Notebook AI audio podcast and an explainer slide show are available for this story beneath.

1. What Is a Patent Foramen Ovale?

Before birth, the foramen ovale is a vital foetal opening between the right and left atria, allowing oxygen-rich placental blood to bypass the inactive lungs. After the first breath, pressure in the left atrium increases, closing the flap naturally.

In around 25% of adults, the flap does not seal fully — this persistent communication is called a Patent Foramen Ovale (PFO).

2. Why Does PFO Matter?

While often silent, a PFO can allow blood to bypass the lungs, especially during short-lived increases in right atrial pressure — for example, while coughing, sneezing, straining, or diving.

This right-to-left shunt permits unfiltered material (e.g., venous thrombi, bubbles, vasoactive compounds) to cross into the systemic circulation and reach the brain, spinal cord, or retina, potentially causing serious events.

3. PFO and Cryptogenic Stroke or TIA: When Is Closure Indicated?

a. Clinical Trial Evidence

Several randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and meta-analyses have shown that PFO closure reduces recurrent ischaemic stroke in patients with prior cryptogenic stroke and high-risk PFO features:

- The CLOSE trial showed zero recurrent strokes over 5 years in patients with large shunts or atrial septal aneurysms (ASA) who underwent PFO closure, versus 4.9% with antiplatelet therapy alone.¹

- The DEFENSE-PFO trial showed a significant reduction in stroke or TIA with closure versus medical therapy in patients with high-risk PFO features.²

- A meta-analysis of six RCTs confirmed long-term stroke risk reduction, especially in younger patients with large shunts or ASA.³

- A pooled patient-level analysis showed approximately 60% relative risk reduction in stroke with closure compared to medical therapy.⁴

While closure increased the risk of transient atrial fibrillation, the net benefit favoured closure for stroke prevention in carefully selected patients.

b. Guidelines and Recommendations

- The American Academy of Neurology (AAN) recommends considering PFO closure in patients under 60 with cryptogenic stroke and high-risk PFO anatomy, after a thorough workup excludes other causes.⁵

- The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) also recommends closure for cryptogenic stroke in selected younger patients with large right-to-left shunts or ASA.⁶

- The American Heart Association (AHA) supports closure in those aged <60 with cryptogenic stroke and high-risk anatomy. For patients ≥60 years, data are insufficient, and decision-making should be individualised.⁷

c. Summary: When to Consider Closure

Closure is indicated in patients with:

- Cryptogenic stroke or TIA, and

- Age under 60, and

- High-risk PFO anatomy (large shunt or ASA), and

- No alternative stroke mechanism identified.

In patients over 60, PFO closure is not routinely recommended, though ongoing trials are investigating its benefit in older groups.⁸

4. PFO in Divers and Decompression Illness

Divers with a PFO may develop decompression illness when nitrogen bubbles pass through a right-to-left shunt and enter the arterial circulation. This can cause neurological injury despite following proper ascent protocols.

Professional divers with recurrent decompression sickness may be screened for PFO, and closure may be considered for occupational safety.⁹

5. PFO and Transient Global Amnesia (TGA)

Some studies suggest a link between TGA and PFO, especially in patients with right-to-left shunts. Microemboli passing through the PFO may transiently affect the hippocampus, resulting in sudden-onset memory loss.¹⁰

Although causal evidence is limited, cardiologists may investigate PFO in recurrent, unexplained TGA, particularly in younger patients.

6. PFO and Migraine: Controversy Explained

Early anecdotal reports — particularly among divers who underwent PFO closure — suggested migraine relief, especially in those with aura.¹¹

This led to several randomised trials:

- MIST (UK): No significant reduction in migraine with PFO closure.¹²

- PRIMA (Europe): No benefit in migraine days; possible improvement in aura subgroups.¹³

- PREMIUM (USA): Missed its primary endpoint but showed modest improvements in migraine days and more complete remission in some patients.¹⁴

A pooled patient-level meta-analysis confirmed a small but significant reduction in migraine days and attacks, especially in patients with aura.¹⁵

However, high heterogeneity, modest effect size, and low certainty of evidence mean that guidelines do not recommend routine PFO closure for migraine:

- SCAI 2022: Against routine closure for migraine alone (very low certainty).¹⁶

- AAN 2020: Closure not advised for migraine without stroke.⁵

7. How Cardiologists Diagnose PFO: The Bubble Study

The bubble contrast echocardiogram (also called a bubble study) is the gold standard for detecting right-to-left shunting:

Step-by-Step:

- Prepare a mix of:

- 5 mL of the patient’s blood

- 1 mL of air

- 3 × 10 mL syringes of saline

Agitate rapidly using a three-way stopcock to create microbubbles.

- Inject into a peripheral vein during echocardiographic imaging.

- The patient performs a Valsalva manoeuvre — forceful exhalation against a closed airway.

- On release, if a PFO is present, microbubbles can be seen crossing from the right atrium to the left atrium within 3–5 heartbeats.

The study can grade the shunt and identify timing, confirming whether the communication is atrial or pulmonary in origin.

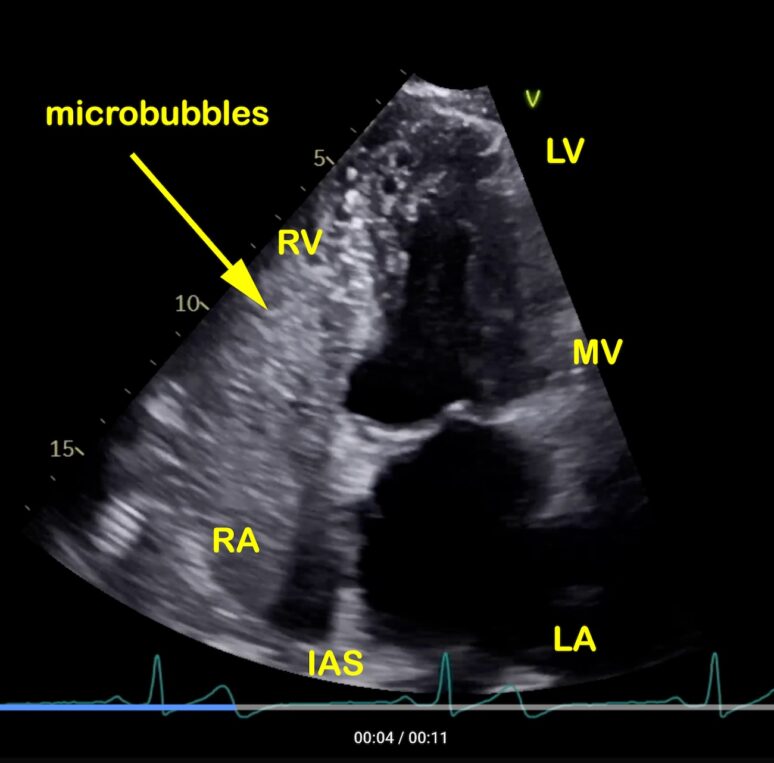

Pre valsalva echocardiogram images of a patient referred following a cryptogenic stroke where our bubble study showed a large PFO

A single frame from an echocardiogram showing the apical 4 chamber view of the heart during normal breathing following injection of agitated saline/blood/air mix into a vein in left arm. Left ventricle (LV), right ventricle (RV), mitral valve (MV)m, right atrium (RA) and left atrium (LA). Whereas the cavity of the LA and LV are free from any microbubbles, the blood mixed with microbubbles arriving into the RA and RV shows as echodense (white) signal. No bubbles are seen in the LA or LV in this frame. However the movie below does show a few microbubbles in the left heart after a few heart beats, indicating a possible communication between the right and left heart. Small communications (pin hole size) are seen in 25% of the population and represent no significant hazard.

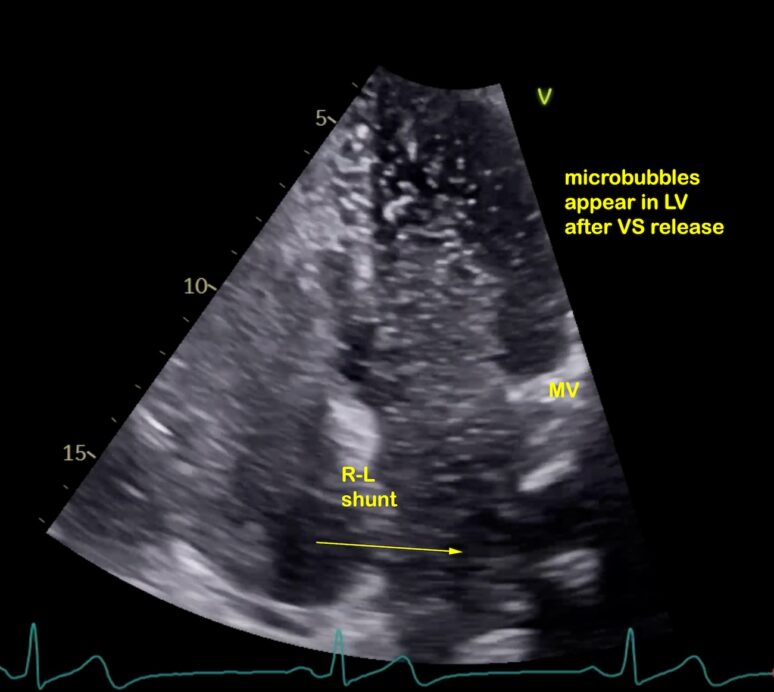

Post valsalva release

A single frame from an echocardiogram, showing the apical four-chamber view of the heart, moments after the patient performs a Valsalva manoeuvre with release. This breathing exercise temporarily increases right atrial pressure above left atrial pressure. In the presence of a significant patent foramen ovale (PFO), this pressure gradient causes the interatrial flap to open, allowing blood to pass from the right atrium into the left atrium. As right atrium has been filled with microbubbles (contrast injection), these can be seen passing into the left atrium in both the single frame (arrowed) and movie below. The extent of this shunt reflects the size of the interatrial communication and helps determine the future risk of paradoxical embolism — where a clot transitions from the venous to the arterial system via the PFO, potentially causing systemic embolization.

8. Summary

- A PFO is common and usually benign.

- In younger patients with cryptogenic stroke or TIA and large right-to-left shunts, PFO closure is effective in reducing stroke recurrence.

- Diving-related decompression illness and some cases of TGA may also be linked to PFO.

- The link between migraine and PFO remains controversial; closure is not routinely advised.

- A bubble echocardiogram is used to detect and grade a PFO.

- Guidelines strongly support individualised decision-making, based on age, stroke type, and anatomical findings.

References

- Mas JL, Derumeaux G, Guillon B, et al. Patent foramen ovale closure or anticoagulation vs. antiplatelets after stroke. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(11):1011–21.

- Lee PH, Song JK, Kim JS, et al. Cryptogenic stroke and high-risk patent foramen ovale: the DEFENSE-PFO trial. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;71(20):2335–42.

- Turc G, Calvet D, Guérin P, et al. Long-term effectiveness and safety of PFO closure vs antithrombotic therapy: meta-analysis of six RCTs. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(39):3813–22.

- Kent DM, Saver JL, Kasner SE, et al. Treatment effects in pooled analysis of PFO closure trials. JAMA. 2021;326(22):2277–86.

- Messé SR, Kasner SE, Carroll JD, et al. Practice advisory update summary: PFO and secondary stroke prevention. Neurology. 2020;94(20):876–85.

- Pristipino C, Sievert H, D’Ascenzo F, et al. European position paper on the management of PFO. Eur Heart J. 2019;40(38):3182–95.

- Elkind MSV, et al. AHA/ASA 2022 stroke guidelines: secondary prevention. Stroke. 2022;53(7):e282–e361.

- Choi JY, et al. PFO closure in older adults with cryptogenic stroke. J Stroke. 2022;24(1):60–8.

- Wilmshurst PT, Byrne JC, Webb-Peploe MM. Relation between interatrial shunts and decompression illness in divers. Lancet. 1989;2(8675):1302–6.

- Sedlaczek O, et al. TGA and hippocampal lesions on DWI: possible link with PFO? Brain. 2004;127(3):655–63.

- Wilmshurst PT, Nightingale S, Walsh KP, Morrison WL. Migraine improvement after closure of cardiac shunts. Lancet. 2000;356(9242):1648–51.

- Dowson AJ, et al. MIST trial: migraine resolution after PFO closure. Circulation. 2008;117(11):1397–404.

- Mattle HP, et al. PRIMA: PFO closure in migraine with aura. Eur Heart J. 2016;37(26):2029–36.

- Tobis JM, et al. PREMIUM: PFO closure and migraine. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2017;70(22):2766–74.

- Mojadidi MK, et al. Pooled analysis of PFO closure trials in migraine. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021;77(6):667–76.

- Kavinsky CJ, et al. SCAI expert consensus on PFO closure. J Soc Cardiovasc Angiogr Interv. 2022;1(3):100039.

Other related articles

- Implantable Loop Recorders (ILRs) in the Investigation of Syncope, Cryptogenic Stroke, TIA, and Transient Global Amnesia

- How AFib can present as a heart attack or stroke

The Naked Heart is an educational project owned and operated by Dr Edward Leatham. It comprises a series of blog articles, videos and reels distributed on Tiktok, Youtube and Instagram aimed to help educate both patients and healthcare professionals about cardiology related issues.

If you would like to receive email notification each week from the Naked Heart, follow me on social media or please feel free to subscribe to the Naked Heart email notifications here