An article written by Dr Edward Leatham, Consultant Cardiologist

For busy people, or to tune in when on the move, Google Notebook AI audio podcast and an explainer slide show are available for this story beneath.

Tags: VAT, Metabolic Health, MASLD, search website using Tags to find related stories.

Most cholesterol in the blood travels inside protein-based particles called lipoproteins. These include chylomicrons, very low-density lipoproteins (VLDL), intermediate-density lipoproteins (IDL), low-density lipoproteins (LDL), and high-density lipoproteins (HDL).

All, except HDL, can contribute to the build-up of fatty plaques in arteries — the process known as atherosclerosis.

Traditional cholesterol tests measure how much cholesterol is present by mass. In the UK this is generally reported as total concentration of cholesterol type in serum expressed in mmol/L. Modern tests can be used to measure the number and type of particles carrying that cholesterol.

This option can provide a more accurate picture of cardiovascular risk in some of our patients.

🧪 The NHS “Non-HDL Cholesterol”

In the NHS, the non-HDL cholesterol value is calculated automatically in every lipid profile.

It’s simply:

\text{Non-HDL-C} = \text{Total cholesterol} – \text{HDL cholesterol}

This represents the total amount of cholesterol carried by all the potentially harmful particles — LDL (including sdLDL), VLDL, IDL, and lipoprotein(a).

- It’s a simple and practical measure.

- It correlates well with ApoB, but remains a cholesterol-mass estimate, not a particle count.

🔬 ApoB — Counting the Particles That Matter

Every atherogenic lipoprotein particle carries one molecule of apolipoprotein B (ApoB).

That means measuring ApoB gives you a direct count of how many cholesterol-carrying particles are circulating in the blood — not just how much cholesterol they contain.

A high ApoB means too many particles, even if your LDL-C number looks normal.

This is particularly common in people with:

- Type 2 diabetes

- Insulin resistance

- High visceral fat (VAT)

- Metabolic syndrome

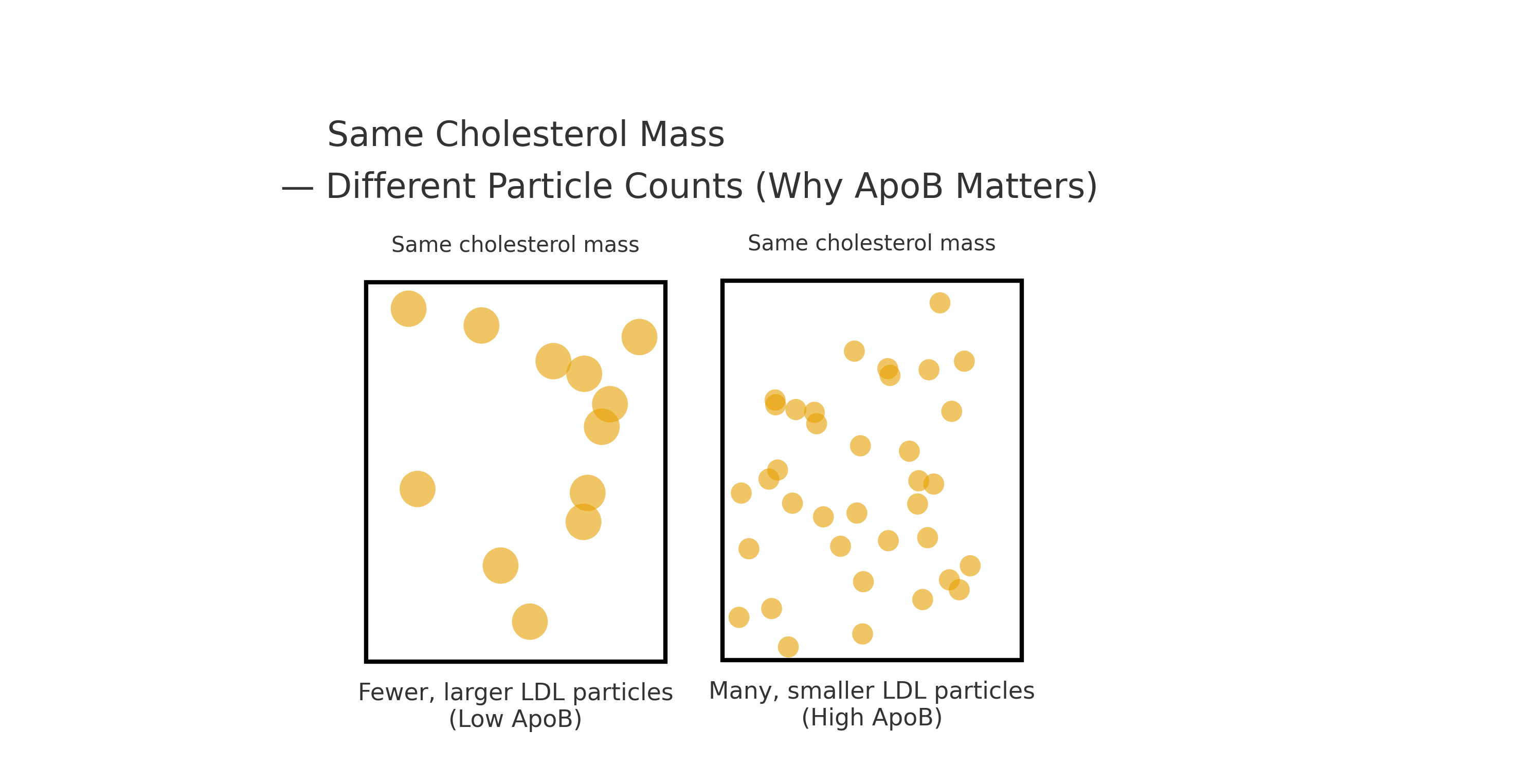

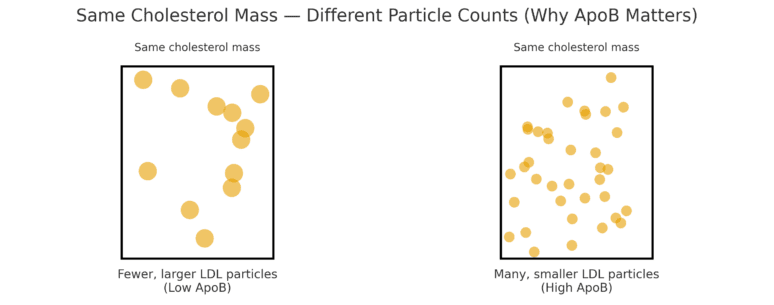

🧩 Why the Number of Particles Matters — Understanding the Image

This picture shows two people who both have the same amount of cholesterol in their blood, but the cholesterol is carried very differently:

Left side: the cholesterol is packed into fewer, larger LDL particles.

Each particle carries plenty of cholesterol, so there are not many particles overall.

→ This person has a lower ApoB level and lower cardiovascular risk.

Right side: the same amount of cholesterol is spread across many smaller LDL particles.

Each particle carries less cholesterol, so the body needs more particles to transport the same total.

→ This person has a higher ApoB level, meaning more smaller particles circulating and greater chance of them entering artery walls.

Even though both have the same total cholesterol, the person on the right has many more opportunities for cholesterol to stick to arteries, increasing long-term risk.

That’s why modern tests such as ApoB — which count the particles — can identify hidden risk that traditional cholesterol tests might miss.

In these states, LDL particles are often smaller and cholesterol-depleted, but more numerous — and it’s the number of small particle LDLs that drives most cardiovascular risk.

⚠️ Small Dense LDL — the Most Dangerous Fraction

Small dense LDL (sdLDL) particles are the most atherogenic type of LDL.

They are:

- Smaller and heavier

- Stay in the bloodstream longer

- More likely to oxidise and enter artery walls

High sdLDL is typical of metabolic syndrome, diabetes, and high triglyceride states linked to visceral fat.

Because sdLDL testing is specialised, the ApoB level and the LDL-C : ApoB ratio can be used to estimate particle size predominance:

| Pattern | LDL-C : ApoB Ratio | Particle Type |

|---|

| High ratio | Larger, cholesterol-rich LDL | Pattern A (lower risk) |

| Low ratio | Small, cholesterol-poor LDL | Pattern B (higher risk) |

📊 Comparing ApoB and sdLDL Measurements

| Feature | ApoB Assay | sdLDL Measurement |

|---|

| What it counts | Total number of atherogenic particles (LDL, sdLDL, VLDL, IDL, Lp(a)) | Cholesterol within small dense LDL particles only |

| Particle size sensitivity | Not affected by particle size; it’s a count | Focuses on smallest, densest LDL |

| Clinical value | Strong predictor of cardiovascular risk | Especially valuable in metabolic and insulin-resistant states |

| Testing method | Blood test (immunoassay or NMR) | Specialised: electrophoresis or sdLDL-C assays |

| Relationship | High ApoB = many particles, often with sdLDL excess | High sdLDL and high ApoB often coexist but don’t always overlap |

🇬🇧 Table 1. UK Reference and Risk Ranges for Lipoprotein Markers (Dual Units)

| Marker | Units (UK / US) | Healthy / Target Range | Moderate Risk Zone | High / Atherogenic Risk Zone | Clinical Notes / Sources |

| LDL-cholesterol (LDL-C) | mmol/L (mg/dL) | < 3.0 (< 116)¹ | 3.0–4.0 (116–155) | ≥ 4.0 (≥ 155) or > 1.8 (> 70) if CVD² ³ | Primary treatment target; NICE goal ≤ 1.8 mmol/L in CVD. |

| Non-HDL-cholesterol (Non-HDL-C) | mmol/L (mg/dL) | < 4.0 (< 155)¹ | 4.0–5.0 (155–193) | > 5.0 (> 193) or > 2.6 (> 100) if CVD² ³ | Reflects all atherogenic cholesterol; practical NHS marker. |

| Apolipoprotein B (ApoB) | g/L (mg/dL) | ≤ 1.00 (≤ 100)⁴ ⁶ | 0.90–1.10 (90–110) | > 1.10 (> 110) or > 0.80 (> 80) if CVD⁴–⁶ | Counts atherogenic particles; better risk marker than LDL-C. |

| Small Dense LDL-cholesterol (sdLDL-C) | mmol/L (mg/dL) | < 1.0 (< 38.6)⁷ | 1.0–1.2 (38–46) | > 1.2 (> 46) or > 0.9 (> 35) if CVD⁷ ⁸ | Most atherogenic LDL fraction; raised in diabetes and high VAT. |

Summary of targets:

- Lower targets = higher cardiovascular protection.

- For established CVD, aim for:

- LDL-C ≤ 1.8 mmol/L (≤ 70 mg/dL)

- Non-HDL-C ≤ 2.6 mmol/L (≤ 100 mg/dL)

- ApoB ≤ 0.80 g/L (≤ 80 mg/dL)

📈 Table 2. LDL-C : ApoB Ratio — Surrogate Marker of LDL Particle Size

| LDL-C : ApoB Ratio (dimensionless) | Quick SI Band (mmol/L ÷ g/L) | Interpretation / Pattern | Typical LDL Type |

|---|

| > 1.3 | > 3.37 | Large, buoyant LDL (Pattern A) | Low sdLDL burden |

| 1.0 – 1.3 | 2.59 – 3.37 | Mixed population (Pattern A/B) | Moderate sdLDL |

| 0.9 – 1.0 | 2.33 – 2.59 | Small dense LDL (Pattern B) | High sdLDL |

| < 0.9 | < 2.33 | Severe sdLDL predominance | Very high risk |

🧮 Quick UK rule:

divide the LDL-C cholesterol in mmol/L / (the Apo B in g/L x 2.59)

Examples:

- LDL-C 3.0 mmol/L, ApoB 1.0 g/L → 3 / (1 × 2.59) = 1.16 → Normal / mixed pattern

- LDL-C 5.0 mmol/L, ApoB 1.2 g/L → 5 / (1.2 × 2.59) = 1.61 → Large LDL, low sdLDL fraction

🩺 Practical Summary

| Marker | What It Reflects | Why It Matters | Healthy / Target Range |

|---|

| LDL-C | Cholesterol within LDL particles | Primary NHS target | < 3.0 mmol/L (< 116 mg/dL) |

| Non-HDL-C | All cholesterol in harmful particles | Practical NHS marker | < 4.0 mmol/L (< 155 mg/dL) |

| ApoB | Number of cholesterol-carrying particles | Most accurate risk measure | ≤ 1.00 g/L (≤ 100 mg/dL) |

| sdLDL-C | Cholesterol in smallest LDLs | Identifies metabolic risk | < 1.0 mmol/L (< 38 mg/dL) |

| LDL-C : ApoB ratio | Cholesterol per LDL particle | Indicates particle size (sdLDL load) | > 1.0 desirable |

🧠 Take-Home Message

- The NHS non-HDL-C test gives a good overall measure of atherogenic cholesterol.

- ApoB adds precision by counting particles, not just measuring cholesterol.

- sdLDL-C and the LDL-C : ApoB ratio reveal particle quality — the difference between large and small LDL.

- Combining these tests gives a clearer picture of cardiovascular risk, especially in people with metabolic syndrome, diabetes, or visceral fat accumulation.

References

¹ Heart UK – Understanding your cholesterol test results

² NICE NG238 (2023) – Cardiovascular disease: risk assessment and lipid modification

³ RUH Bath – Lipid management (PATH-018, 2023)

⁴ Synnovis Labs – ApoB Test Information (2024)

⁵ Medscape – Apolipoprotein B Overview (2024)

⁶ Sniderman AD et al. Eur Heart J. 2023;44(21):1930–1944

⁷ Luo J et al. Atherosclerosis. 2024;387:123–132

⁸ Musunuru K et al. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73(12):1610–1623

Related posts

- The Hidden Culprit Behind Heart Disease: Small Dense LDL and the Fat You Can’t See