An article written by Dr Edward Leatham, Consultant Cardiologist

An AI audio construct is available as a podcast fo rthis story below.

Tags: Mens Health, Visceral Fat, Coronary heart disease, search website using Tags to find related stories.

Most men over 30 will recognise the slow but steady expansion of the waistline. Whether you call it a spare tyre, a dad bod, or just a bit of extra padding, not all belly fat is created equal — and not all of it is harmless.

Some types of abdominal fat are mostly cosmetic. Others are dangerous, inflammatory, and metabolically active — the kind of fat that silently drives heart attacks, strokes, dementia, and even advanced cancers.

Let’s break down the three main culprits behind the male belly — and what you can do about them.

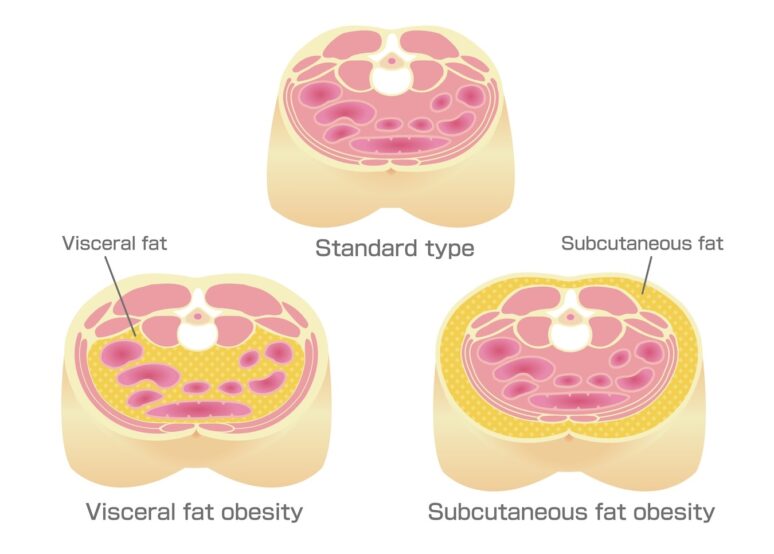

Type of obesity illustration. Abdominal sectional View. (visceral fat , subcutaneous fat)

Fat distribution matters

Research has established that the metabolic syndrome and cardiovascular/cancer risk are very clearly dependent on which body compartment surplus adipose is distributed.

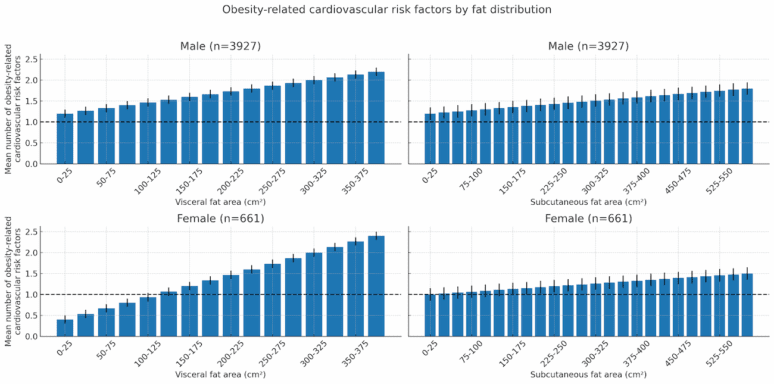

This figure, based on Figure 1 from a review article by Ken Shida et al in 2011 (reference 7 below), illustrates a more powerful association between the number of obesity-related risk factors and visceral than subcutaneous fat.

🔹 1. Subcutaneous Fat — The Flabby Outer Layer

This is the soft fat just under the skin. You can pinch it, and it tends to gather around the lower abdomen and love handles.

- Why it appears: Too many calories, too little movement, and dropping testosterone levels with age.

- Health risk? Low to moderate — more of a cosmetic issue, but a sign your metabolism may be slowing.

- What helps:

- Moderate caloric restriction

- Regular aerobic activity (brisk walking, swimming)

- Strength training to increase lean muscle mass

🔹 2. Visceral Fat — The Killer Fat You Can’t See

Unlike flabby subcutaneous fat, visceral fat lies deep inside the abdomen, packed around vital organs like the liver, pancreas, and intestines. You can’t pinch it — but you can feel it in a hard, protruding belly that’s often mistaken for “bloating” or “beer gut”.

- Why it’s deadly:

- Visceral fat pumps out inflammatory chemicals

- It drives insulin resistance, high triglycerides, low HDL, and fatty liver

- It’s linked to:

- 💥 Heart disease and stroke

- 🧠 Dementia and cognitive decline

- 🦠 Advanced prostate and colorectal cancers

- Who’s at risk?

- Men over 40

- Anyone with a waist-to-height ratio >0.5

- People with normal BMI but poor metabolic health

- How to spot it:

- Waist-to-height ratio

- DEXA scans (moderate accuracy)

- Low-dose CT scans (gold standard for visceral fat and liver fat, see examples below.

- What helps:

- Low-glycaemic, protein-rich diet

- High-intensity interval training (HIIT)

- GLP-1 mimetic therapy (e.g. semaglutide) for high-risk individuals

- Reducing alcohol and improving sleep

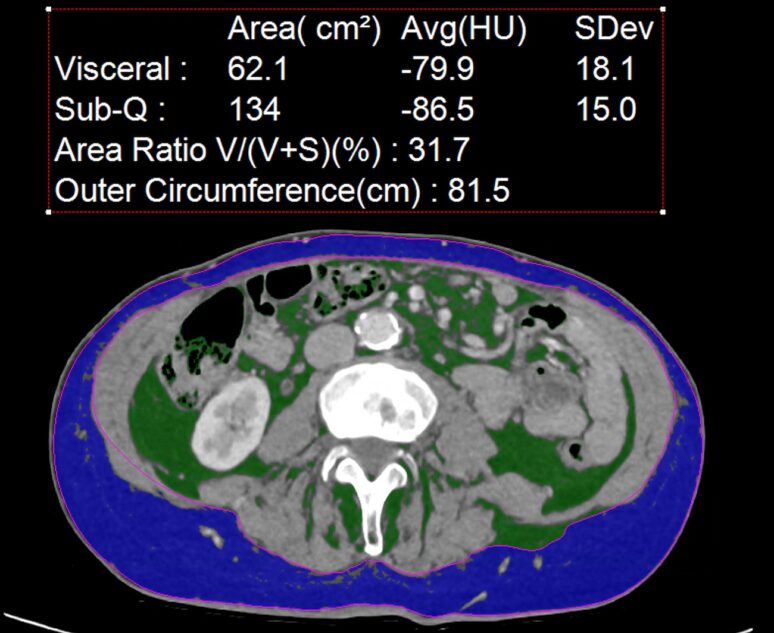

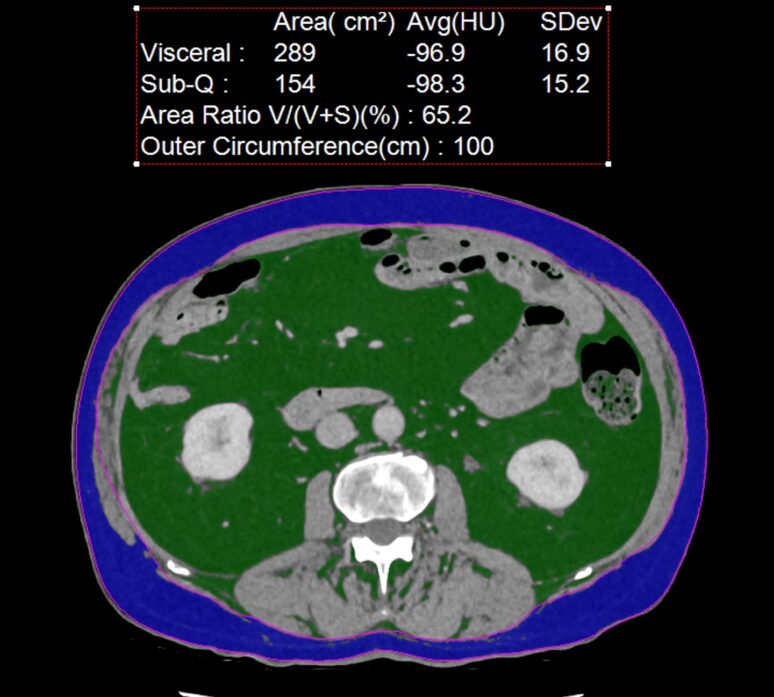

Example of CT scans showing low (panel A) and high (panel B) visceral fat

Image processing software of a single slice of two different male patients abdominal CTs at the level of third lumbar vertebrae.

This allows the detection and quantification of fat tissue in subcutaneous (Blue) and visceral compartments (Green). It will be apparent that, whereas the subcutaneous fat is roughly similar 134 versus 154 cm/2, there is a large difference in the visceral fat of the patient in panel B.

🔹 3. Poor Muscle Tone and Bowel Gas —The Forgotten Factor

Not all belly bulges are caused by fat. Loss of abdominal muscle tone is a key contributor, especially in sedentary men and post-injury recovery.

- What it looks like:

- A saggy or bloated lower belly

- Worsens after meals

- No obvious “fat” on scan

- Why it matters:

- Poor tone affects posture, core stability, and lower back health

- May mask real fat loss or give a distorted shape

- What helps:

- Core stability work: planks, leg raises, dead bugs

- Diaphragmatic breathing

- Pilates, yoga, or physio-based strength work

Another short term cause of a larger waist measurement is trapped gas – common after air flight where cabin pressure is lowered or after meal contents that produce more methane. These explain why your belly may bloat for a few days after travel or an unusual meal.

🔍 Quick Guide: Which Belly Is Which?

| Belly Type | Feel | Risk Level | Looks Like |

|---|

| Subcutaneous | Soft, pinchable | Low–moderate | Floppy or squishy |

| Visceral | Hard, tight | High | Firm, rounded protrusion |

| Poor Tone | Soft but not fat | Low (functional) | Bloating or sagging |

✅ How to Take Control of Your Waistline

No matter which type of belly you’re dealing with, you can improve it — and your health — with the right combination of interventions.

Key steps:

- 🥗 Cut back on sugar and processed carbs

- 🍽️ Eat enough protein and create a mild calorie deficit

- 🏃 Mix cardio and resistance training

- 🔬 Consider GLP-1 therapy if high-risk or insulin-resistant

- 🧘 Focus on breath, posture, and core engagement

- 📏 Track progress using waist-to-height ratio or scan-based tools

⚠️ Final Thought: It’s Not Just About Looks

Your belly might just be a result of sitting too much or eating too well — but it could also be a marker of deeper risk. Especially if it’s firm and central, it’s worth digging deeper.

In short:

Is your belly just flabby — or is it killer fat hiding in plain sight?

To find out more on how we measure and treat visceral fat see our related articles or our metabolic toolkit page

Other related articles

- From Genes to Greens: How DNA Shapes Your Nutritional Needs

- Effects of different exercise types on visceral fat in young individuals with obesity aged 6–24 years old: A systematic review and meta-analysis 2022

- Clinical significance of visceral adiposity assessed by computed tomography: A Japanese perspective: 2014

- Visceral and ectopic fat, atherosclerosis, and cardiometabolic disease: a position statement 2019

- Body fat distribution on computed tomography imaging and prostate cancer risk and mortality in the AGES-Reykjavik study 2019